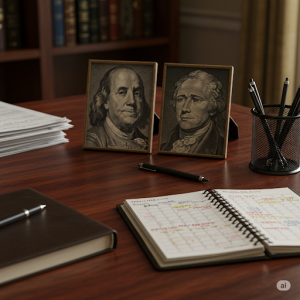

Mr. Cool and Mr. Duel: What We Can Learn From Franklin and Hamilton About Preparation

By: Ira S. Bergman

Florida Supreme Court Certified Circuit Civil Mediator

There are many reasons why mediations end in impasse. But, in my experience, the lack of preparation (by one side or sometimes both) often plays a key role. It therefore seems appropriate to delve further into the increasingly lost art of preparation. In doing so, I find inspiration in Ben Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, perhaps two of the most prepared individuals the world has ever known.

preparation. In doing so, I find inspiration in Ben Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, perhaps two of the most prepared individuals the world has ever known.

Franklin and Hamilton have always struck me as the most approachable of the Founding Fathers (and not merely because the latter inspired a Tony award-winning Broadway musical). I like to think that you could sit down with these two towering historical figures, have a beer and actually enjoy yourself. Washington? A little too stoic, with a bad temper.1 Jefferson? A bit cold and reserved.2 Adams? Too stuffy and sanctimonious.3

Franklin, by contrast, was the epitome of 18th Century cool. He has been referred to by the National Constitution Center as “America’s first rock star.”4 By almost all accounts, Franklin was charming, naturally sociable, and witty. In France, Franklin was adored, and his adventures (or perhaps exploits) there remain legendary. Hamilton came from a disadvantaged upbringing on a tiny island in the Caribbean. Through sheer grit, determination and intelligence, he made his way from the Caribbean to Washington’s side during the Revolutionary War and eventually to the Constitutional Convention, where he helped write the U.S. Constitution.

Much can be learned from Ben Franklin about the importance of preparation. Before going to work each morning, Franklin would prepare for the day ahead by asking a simple but important question – “What good shall I do this day”? Then he’d pick a virtue5 to focus on, and begin to “contrive day’s business, and take the resolution of the day” i.e., to plan his day.

Perhaps no better example of Hamilton’s commitment to preparation is the Federalist Papers. The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays published in 1787-1788 in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution. Although some of the essays were penned by James Madison6 and John Jay7, Hamilton wrote an impressive 51 of the 85 essays. In a very real sense, Hamilton was preparing the country for the ratification of the Constitution and a new form of government.

If mediation is to be successful, it requires preparation by both sides. It therefore surprises me when attorneys and/or parties come to mediation unprepared. For some reason, these folks (who would never dream of coming to trial unprepared) seem to believe that they can “wing it” at mediation and still settle the case. While settlements are occasionally reached despite lack of preparation, it more often than not leads to impasse. But why?

At mediation, each side should be analyzing the probability of various outcomes of motion practice and/or a future trial and the financial implications of each, and then arriving at an expected value of the case based upon these considerations. This calculus should not be set in stone. Rather, it should continually be adjusted and updated based upon the dialogue at mediation concerning the applicable facts and law. Absent preparation, one or both sides will be unable to accurately measure expected value because this dialogue will not be sufficiently robust.

While counsel may come to mediation prepared to address the merits of their respective cases, they all too often fail to take a crucial step in their preparation, i.e., predicting the arguments that will be made by their adversary and having a rebuttal at the ready. But how can one expect settlement negotiations to bear fruit if he or she does not have at least a colorable argument as to why the other side’s position is factually or legally incorrect? Even if the other side dismisses such an argument, it will at least have provided food for thought which could influence that side’s expected value calculation. By the same token, the lack of a rebuttal will likely be viewed as a concession.

Of course, preparation takes time and costs money. It involves the expenditure of attorney time and potentially the involvement of experts. But, it is also true — as I have hopefully illustrated above — that preparation increases the likelihood of settlement. A settlement generally results in great savings of time and money, especially if the case is on the heels of trial.

And so, I submit that preparation is a balancing act. I might suggest preparing enough so that it makes financial sense given the value of the case, the expected costs of continuing to litigate and your intuition as to how much influence your preparation will have on the other side’s expected value calculation — in other words, a “reasonable” amount.

Preparation is not only important for the attorneys, but also for the parties and/or their representatives. It is imperative that counsel prepare their clients for mediation, since they are the ultimate decisionmakers. This preparation, at a minimum, should include an explanation of the mediation process (if they are not thoroughly familiar with it) and a discussion concerning both the good and the not-so-good aspects of the case.

During this preparation, clients should also be presented with the arguments likely to be raised by the other side and how counsel plans to respond to these arguments, including the documents, photos or other information that will be used. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, counsel should set expectations in terms of a likely settlement range so that rational and informed decisions can be made at mediation.

Ben Franklin and Alexander Hamilton died well before the age of mediation, but their towering achievements live on. It’s probably fair to say that these achievements would not have been possible without their extraordinary commitment to preparation. To borrow a quote attributed to Franklin, “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”8While an entirely new form of government might not hang in the balance at your next mediation, it might nevertheless be worthwhile to draw inspiration from the men on the $10 and $100 bills — as the fate of many such bills may rest upon the outcome.

1 In recounting Washington’s reaction when he heard that one of his generals, Charles Lee, was retreating from the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse in 1778, Charles Scott (another of Washington’s generals) said, “He swore that day till the leaves shook on the trees. Charming! Delightful! Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since. Sir, on that memorable day he swore like an angel from heaven!.”

2 1825. (Robley Dunglison) “At all times dignified, and by no means easy of approach to all, was generally communicative to those on whom he could rely. In his own house he was occasionally free in his speech, even to imprudence, to those of whom he did not know enough to be satisfied that an improper use might not be made of his candor. … Mr. Jefferson was not a man who could be regarded as an eminent conversationalist. He was rather reserved; and did not often enter into great questions – political or moral – in my presence.”

3 A friend of Adams (Jonathan Sewall) once said of him, “He cannot dance, drink, game, flatter, promise, dress, swear with the gentlemen, and small talk and flirt with the ladies; in short, he has none of those essential arts or ornaments which constitute a courtier. There are thousands who, with a tenth of his understanding and without a spark of his honesty, would distance him infinitely in any court in Europe.”

4 See Blog Post, America’s first rock star: Benjamin Franklin in France (Nat. Constitution Ctr. Dec. 17, 2015).

5 Franklin came up with a list of 13 “virtues” of life: Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity and Humility.

6 Madison went on to become the 4th President of the United States.

7 After the establishment of the new federal government, President George Washington appointed Jay to be the first Chief Justice of the United States.

8 Although there is some dispute about whether Franklin actually came up with this expression, it is undisputed that he lived his life by this sentiment.